|

|

|

About Horned Lizards

|

|

Text by Dr. Wendy Hodges

Introduction

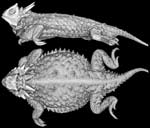

Click on images for larger views. Horned lizards, genus Phrynosoma, are fascinating, unique and easily recognized animals. They were introduced to European audiences in 1651 through the writing of a Spaniard, Francisco Hernandez. During his travels in Mexico from 1570-1577, Hernandez was fortunate to observe a living horned lizard squirt blood from its eyes. He noted this unique defensive behavior in his report on the first scientific expedition to Mexico by Spain. Nearly two centuries later, in 1828, Wiegmann coined the formal scientific generic name Phrynosoma. Click on images for larger views. Horned lizards, genus Phrynosoma, are fascinating, unique and easily recognized animals. They were introduced to European audiences in 1651 through the writing of a Spaniard, Francisco Hernandez. During his travels in Mexico from 1570-1577, Hernandez was fortunate to observe a living horned lizard squirt blood from its eyes. He noted this unique defensive behavior in his report on the first scientific expedition to Mexico by Spain. Nearly two centuries later, in 1828, Wiegmann coined the formal scientific generic name Phrynosoma.

Images of horned lizards can be found in the artwork and pottery of Native Americans, on tags of high-end outdoor clothing, as stuffed animals in toy stores, on wood carvings at local festivals… they seem as popular as ever. But however common they may be in culture, they are becoming increasingly uncommon in nature. Declining populations are primarily associated with landscape-scale human disturbances such as urbanization and agriculture. Unfortunately, the popularity and habits of horned lizards make them highly susceptible to large-scale collection for the pet trade; they make terrible pets, for reasons discussed below. Images of horned lizards can be found in the artwork and pottery of Native Americans, on tags of high-end outdoor clothing, as stuffed animals in toy stores, on wood carvings at local festivals… they seem as popular as ever. But however common they may be in culture, they are becoming increasingly uncommon in nature. Declining populations are primarily associated with landscape-scale human disturbances such as urbanization and agriculture. Unfortunately, the popularity and habits of horned lizards make them highly susceptible to large-scale collection for the pet trade; they make terrible pets, for reasons discussed below.

Phylogenetic History

Horned lizards are iguanian reptiles traditionally included with other lizards known as sceloporines. Although they are lizards, horned lizards are often called 'horned toads' or 'horny toads' because of their wide and flat body shape. In fact, the generic name Phrynosoma is derived from Greek terms for toad-bodied ('phrynos' means 'toad', 'soma' means 'body'). More recently, sceloporines were elevated to family level and named Phrynosomatidae. Members of this group include the horned lizards, Phrynosoma; the sand and earless lizards, Uma, Callisaurus, Cophosaurus and Holbrookia; and the spiny, rock, tree, brush, and side-blotched lizards, Sceloporus, Sator, Petrosaurus, Urosaurus, and Uta. Phrynosoma is more closely related to the sand and earless lizards than to other sceloporines. Horned lizards are iguanian reptiles traditionally included with other lizards known as sceloporines. Although they are lizards, horned lizards are often called 'horned toads' or 'horny toads' because of their wide and flat body shape. In fact, the generic name Phrynosoma is derived from Greek terms for toad-bodied ('phrynos' means 'toad', 'soma' means 'body'). More recently, sceloporines were elevated to family level and named Phrynosomatidae. Members of this group include the horned lizards, Phrynosoma; the sand and earless lizards, Uma, Callisaurus, Cophosaurus and Holbrookia; and the spiny, rock, tree, brush, and side-blotched lizards, Sceloporus, Sator, Petrosaurus, Urosaurus, and Uta. Phrynosoma is more closely related to the sand and earless lizards than to other sceloporines.

Phrynosoma is thought to have split from an ancestor shared with the sand lizards during the late Oligocene-early Miocene (23- 30 million years ago, mya). Most horned lizard species are well represented in the fossil record by the Pleistocene (circa 1 mya), P. cornutum is found in the Upper Pliocene (3 mya), and P. douglassii is known from the middle Miocene (15 mya). Three species went extinct in the late Pliocene-early Pleistocene. Today, 16 living species of Phrynosoma inhabit the western half of the North American continent and many of its islands from southern Canada to northern Guatemala.

The wide flat body shape of Phrynosoma is a characteristic that easily distinguishes these lizards from their sister group (the sand lizards) and most other lizards in general. Other characters that set apart the horned lizards include their expanded skulls adorned with parietal (=occipital) and squamosal (=temporal) horns, an expanded sternum with enlarged fontanelle and reduced ribs, and a reduced pectoral girdle, caudal vertebrae, and epipterygoid. The wide flat body shape of Phrynosoma is a characteristic that easily distinguishes these lizards from their sister group (the sand lizards) and most other lizards in general. Other characters that set apart the horned lizards include their expanded skulls adorned with parietal (=occipital) and squamosal (=temporal) horns, an expanded sternum with enlarged fontanelle and reduced ribs, and a reduced pectoral girdle, caudal vertebrae, and epipterygoid.

|

Ecology and Natural History

Horned lizards are myrmecophagous - ant-eating specialists; some species eat essentially nothing else while others eat a variety of arthropods. There is a correspondence between increasing ant content in the diet and shortening of the epipterygoid, reduction of the coronoid process and mandible, lengthening of the tooth rows, and shortening of the teeth. Ants are small and contain much indigestible chitin, so large numbers of them must be consumed. Hence an ant specialist must possess a large stomach for its body size to process a lot of material. When expressed as a proportion of total body weight, the stomach occupies a considerably larger fraction of the animal's overall body mass (e.g., about 13% in Phrynosoma platyrhinos) than do stomachs of all other sympatric desert lizard species. Possession of such a large gut necessitates a tank-like body form, reducing speed and decreasing the horned lizard's ability to escape from predators by flight. As a result, natural selection has favored a spiny body form and cryptic behavior rather than a sleek body and rapid movement to cover.

Horned lizards are myrmecophagous - ant-eating specialists; some species eat essentially nothing else while others eat a variety of arthropods. There is a correspondence between increasing ant content in the diet and shortening of the epipterygoid, reduction of the coronoid process and mandible, lengthening of the tooth rows, and shortening of the teeth. Ants are small and contain much indigestible chitin, so large numbers of them must be consumed. Hence an ant specialist must possess a large stomach for its body size to process a lot of material. When expressed as a proportion of total body weight, the stomach occupies a considerably larger fraction of the animal's overall body mass (e.g., about 13% in Phrynosoma platyrhinos) than do stomachs of all other sympatric desert lizard species. Possession of such a large gut necessitates a tank-like body form, reducing speed and decreasing the horned lizard's ability to escape from predators by flight. As a result, natural selection has favored a spiny body form and cryptic behavior rather than a sleek body and rapid movement to cover.

A wide, flat body form is also thought to enable horned lizards to have large numbers of offspring. Horned lizards are a rather fecund group compared to other lizards: the median clutch size for P. cornutum is 25; P. asio lays 18 eggs on average; P. hernandesi bears up to 16 live young; and P. taurus has an average of 11 offspring. The wide body form provides suitable space for embryos to reside during partial or full development. There are two major groups of horned lizards: one lays eggs (oviparity) while the other gives birth to live young (viviparity). Although the ancestral state is oviparity, two lineages of horned lizards have evolved viviparity (the short-horned group [P. ditmarsi, P. douglassii, P. hernandesi, and P. orbiculare] and a two-species group [P. braconnieri and P. taurus]). Viviparity appears to have evolved twice in the genus, rather than independently in each of the six live-bearing species.

Phrynosoma display a suite of interesting behaviors. Probably the two most unique behaviors are rain-harvesting and blood-squirting. Rain–harvesting is a behavior the lizards exhibit to maximize water uptake when it rains. Rain is infrequent in arid and semi-arid environments where many Phrynosoma species live, and the lizards take advantage of every opportunity to gain water. They obtain some water during digestion of their ant prey, but external water is also important when they can get it. When it rains, a horned lizard will elevate its posterior (tail) end over its head, creating an inclined surface. When rain hits their backs, dorsal scales channel water down the incline toward their heads. They open and close their mandibles, seeming to pump the water down to their mouths.

Blood-squirting is also an odd and interesting behavior that eight species of horned lizards are known to use effectively to deter a specific group of predators – canids (e.g., dogs, foxes and coyotes). When blood comes in contact with a canid’s mouth, the predator shakes its head in obvious protest to the taste. If the predator is holding the lizard in its mouth, it drops it, affording the lizard a chance to escape. This defense must come at quite a cost because many individuals exhibit it only after going through a complete repertoire of other defensive behaviors. Blood-squirting is also an odd and interesting behavior that eight species of horned lizards are known to use effectively to deter a specific group of predators – canids (e.g., dogs, foxes and coyotes). When blood comes in contact with a canid’s mouth, the predator shakes its head in obvious protest to the taste. If the predator is holding the lizard in its mouth, it drops it, affording the lizard a chance to escape. This defense must come at quite a cost because many individuals exhibit it only after going through a complete repertoire of other defensive behaviors.

|

Horned Lizards on DigiMorph

To date, the High-Resolution X-ray CT Facility at The University of Texas has scanned the heads of all thirteen living species of horned lizards (Phrynosoma asio, P. braconnieri, P. cornutum, P. coronatum, P. ditmarsi, P. douglassii, P. hernandesi, P. mcallii, P. modestum, P. orbiculare, P. platyrhinos, P. solare, and P. taurus), the whole body of three species (P. cornutum, P. mcallii and P. taurus) and a developing embryo removed from an adult P. taurus. These scans are part of ongoing research conducted by Dr. Wendy Hodges at The University of California, Riverside. These data are being used for several projects, including the 3D reconstruction of how the ancestor of horned lizards might have looked. The ancestral reconstruction project is an NSF-funded collaborative project between The University of California, Riverside, and the Texas Advanced Computing Center’s Visualization Laboratory at UT Austin.

|

Selected Literature

Brattstrom, B. H. 1955. Pleistocene lizards from San Josecito Cavern, Mexico with description of a new species. Copeia 1955:133-134.

Etheridge, R., 1958. Pleistocene lizards of the Cragin Quarry fauna of Meade County, Kansas. Copeia 1958:94-101.

Etheridge, R., and K. de Queiroz. 1988. A phylogeny of Iguanidae, pp. 283-368. In: Estes, R., Pregill, G. (Eds.), Phylogenetic Relationships of Lizard Families: Essays Commemorating Charles L. Camp. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Frost, D. R., and R. Etheridge. 1989. A phylogenetic analysis and taxonomy of iguanian lizards (Reptilia: Squamata). University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Miscellaneous Publication 81.

Hodges, W. L. 2002. Phrynosoma systematics, comparative reproductive ecology, and conservation of a Texas native. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Texas, Austin.

Howard, C. W. 1974. Comparative reproductive ecology of horned lizards (Genus Phrynosoma) in southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science 9:108-116.

Montanucci, R. R. 1987. A phylogenetic study of the horned lizard genus, Phrynosoma, based on skeletal and external morphology. Los Angeles County Natural History Museum Contributions in Science 113:1-26.

Montanucci, R. R. 1989. The relationship of morphology to diet in the horned lizard genus Phrynosoma. Herpetologica 45:208-216.

Pianka, E. R., and W. S. Parker. 1975. Ecology of horned lizards: a review with special reference to Phrynosoma platyrhinos. Copeia 1975:141-162.

Presch, W. 1969. Evolutionary osteology and relationships of the horned lizard genus Phrynosoma (Family Iguanidae). Copeia 1969:250-275.

Reeder, T. W. 1995. Phylogenetic relationships among phrynosomatid lizards as inferred from mitochondrial ribosomal DNA sequences: substitutional bias and information content of transition relative to transversion. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 4:203-222.

Reeder, T. W., and R. R. Montanucci. 2001. Phylogenetic analysis of the horned lizards (Phrynosomatidae: Phrynosoma): evidence from mitochondrial DNA and morphology. Copeia 2001:309-323.

Reeder, T. W., and J. J. Wiens. 1996. Evolution of the lizard family Phrynosomatidae as inferred from diverse types of data. Herpetological Monographs 10:43-84.

Reeve, W. L. 1952. Taxonomy and distribution of the horned lizard genus Phrynosoma. University of Kansas Science Bulletin 34:817-960.

Rickart, E. A. 1976. A new horned lizard (Phrynosoma adinognathus) from the early Pleistocene of Meade County, Kansas, with comments on the herpetofauna of the Borchers locality. Herpetologica 32:64-67.

Robinson, M. D., and T. R. Van Devender. 1973. Miocene lizards from Wyoming and Nebraska. Copeia 1973:698-704.

Schultze, H. -P., L. Hunt, J. Chorn, and A. M. Neuner. 1985. Type and figured specimens of fossil vertebrates in the collection of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Part II. Fossil Amphibians and Reptiles. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Miscellaneous Publication 177:1-63.

Sherbrooke, W. C., and G. A. Middendorf, III. 2001. Blood-squirting variability in horned lizards (Phrynosoma). Copeia. 2001:1114-1122.

Smith, H. M. 1946. Handbook of Lizards: Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Comstock Publishing Co., Ithaca, New York.

Zamudio, K. R., and G. Parra-Olea. 2000. Reproductive mode and female reproductive cycles of two endemic Mexican horned lizards (Phrynosoma taurus and Phrynosoma braconnieri). Copeia 2000:222-229.

|

|